By: Nasreen Khan, Daniel Vallejo, and Virginia Howell

“Any student reading this document will easily be able to override any difficulties/sadness/obstacles in

life and will be able to gain respect for himself and his family in society.”

Who We Are and the Paper Museum

The Robert C. Williams Museum of Papermaking houses hand papermaking artifacts from around the world. Dard Hunter, a renowned paper historian and founder of the museum, collected many of these objects throughout the early 1900s as he sought to gain more knowledge about this craft. Nearly 100 years later, the museum continues its mission to collect, preserve, increase, and disseminate knowledge about papermaking to the general public. By collaborating with Georgia Tech researchers, and the larger Atlanta community, by using scientific tools, we can unlock hidden information held within the objects, both from a historical and scientific perspective. Recently, two Georgia Tech Postdoctoral Fellows, Nasreen Khan (Paper Museum/RBI) and Daniel Vallejo (School of Chemistry and Biochemistry) sought to uncover more about a loom in the museum’s collection, connected with the history of the Indian subcontinent and Gandhi.

Dard Hunter and Background of the Loom

In the 1930s, Dard Hunter traveled to Asia and the Indian subcontinent (I.e., India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Kashmir) to document hand papermaking techniques and collect tools and paper samples. At that time many people, including Mahatma Gandhi, aimed to revitalize the Indian hand papermaking tradition by supporting and creating schools to teach the craft [1-3]. Dard Hunter visited several papermaking villages and schools, including those helped founded by Gandhi. Hunter brought a loom back to America that was used to weave a chapri (paper-mold cover or screen), but the information of the specific origins of this loom was lost.

What’s Missing?

While Hunter and other researchers documented and studied hand papermaking tools and materials of this region and time, it was primarily from a historical and cultural perspective [1-5]. Much of their focus has been on the plant materials used to make the paper and molds [1-5]. However, some parts of the handmade molds in Asia were known to also use biological materials sourced from animals, such as silk and animal hair [1-4]. Since the exact origin of the loom and the fibers used to construct the paper mold was not known, the museum was interested in learning more about this object.

With scientific tools, the study aimed to understand more about the fibers commonly used in traditional handmade paper-mold covers in the 1930s Indian subcontinent by using scientific tools. With the availability of high-resolution microscopy technologies and historical documentation at Georgia Tech and the Museum, researchers aimed to either prove or disprove whether the origin of preserved fibers on the loom was from an animal and determine with historical context where the loom was acquired.

What we did and what we discovered

Are the Fibers Really Horsehair?

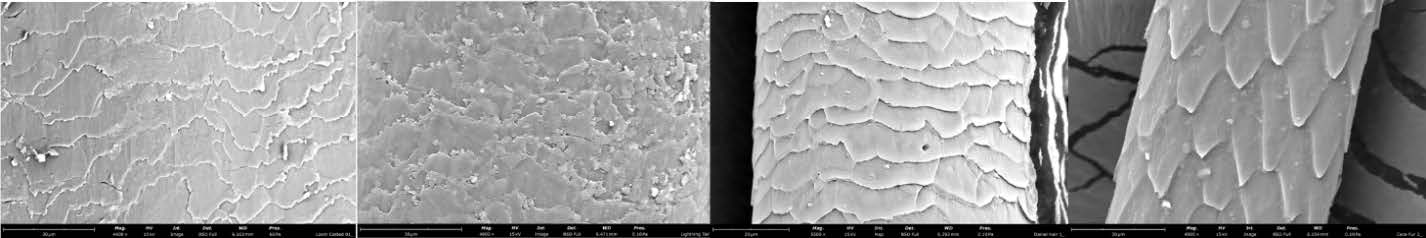

In forensic analysis, typically the first step to identify unknown fiber or hair samples is to conduct microscopy. Microscopy, or the science of using microscopes to view samples & objects that cannot be seen with the naked eye, is the gold standard for analyzing and identifying unknown fibers by comparison to a library of known reference materials. This is possible because hair from different sources or animals have different “morphologies”, or physical features, that help identify their origin. Thanks to the Materials Innovation and Learning Laboratory (MILL), a hub of scientific equipment for hands-on scientific training of undergraduates at Georgia Tech, the researchers were able to use two different microscope techniques: Light microscopy and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). Thanks to Little Creek Farm Conservancy in Decatur and Kristine Parson, the researchers were able to obtain reference materials for tail and mane horsehair from two horses: Angus and Lightening.

By comparing features of the loom fiber to known animal hair: horses, humans, and even a cat, we gained a better idea of how the features of the hair differ between different species, parts of an animal, and even the age of the hair. For example, the average diameter of the hairs was significantly different between the species we measured, and even between the tail and mane of a horse [6]. Some more subtle differences in the scale patterns can be seen on the surface of the cuticles. Additionally, internal structures of the hair like the medulla, and even pigmentation in the cuticle, vary between species but require different microscopy techniques than the two discussed in this work.

While the surface features of the loom fiber and known horsehair look similar, more research is needed to confirm definitely. There are other domesticated animals in the Indian subcontinent including buffalo, oxen, donkeys, and more whose hair is used as textiles and have similar scale patterns.

Something unexpected:

While the research to confidently identify the fiber material as either horsehair or another animal continues, an unexpected discovery was made about the fiber. Based on the data from the light microscope experiments, there is now evidence that a coating was applied to the hair. This discovery is exciting because of Dard Hunter’s reputation as a meticulous record keeper throughout his career cataloging paper and tools, and there was no mention of this coating process on the hair used to weave the mold covers in his book: Papermaking by Hand in India.

Initial Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) analysis, a scientific measurement using wavelengths of light to identify materials by vibrating chemical bonds in molecules, found that the coating was too thin to be able to differentiate what it is made of versus the underlying chemical components of the hair. More advanced and special techniques would be needed to identify the composition of the coating. However, this discovery creates several new and exciting scientific goals, as well as provenance questions about the papermaking process, and that this information may also be historically preserved in the Indian subcontinent.

Where is the Loom from?

To identify where the Loom was from in the Indian subcontinent, we investigated historical and cultural knowledge. The first step was translating an inscription on the base of the loom, in hopes that it may have an identifier. Thanks to Rupal Tamhankar and Priya Devarajan, the inscription was translated to:

“Any student reading this document will easily be able to override any difficulties/sadness/obstacles in life and will be able to gain respect for himself and his family in society.”

The translation suggests that the loom may have been from a papermaking school. To look further into the historical records, the museum turned to original handbound copies of Hunter’s book which includes paper samples made at each of the locations he visited. From his description of chain and laid line patterns and their dimensions on the mold covers from different regions in the Indian subcontinent, the loom is likely from the village of Kalpi in Utter Pradesh, India. In at least one handmade paper sample identified as being made in the village of Kalpi, we can see the 3 chain lines together in the sample with the same pattern as on our mold cover from the loom.

What we discovered and future works

Together, we combined historical, cultural, and scientific knowledge from our diverse team of collaborators and departments at Georgia Tech to redefine the provenance of a foundational object in the museum's care and learned more about the materials of a now historic craft. With analytical techniques, we confirmed that the fibers were hair originating from an animal and additionally found an unexpected coating on them. Future scientific research will involve specialized microscopic analysis to identify the coating, and by leveraging state-of-the-art genomic testing we will be able to confirm the identity of the animal hair as either horse or another domesticated animal native to Indian subcontinent. This investigative process not only revealed accurate information about an object in the historic collection but also provided a template of the process for future scientific inquiries by museum staff to identify historic materials.

Acknowledgements and special thanks to:

Thank you to:

- Nicolas Somers, Blake Moore, and Mark Losego at the MILL

- Bobbi Woolwine, Angus the horse, and Little Creek Farm Conservancy (www.littlecreekfarmconservancy.org)

- Kristine Parson and Lightening the Horse

- Rupal Tamhankar and Priya Devarajan

- Larry Peterson and Patricia Caldwell

- Kelsey Diffley and Cece the cat

A portion of this research was conducted in Georgia Tech’s Materials Innovation & Learning Laboratory (The MILL), an uncommon “make and measure” space committed to elevating research in materials science throughout Georgia Tech. This work is supported in part by the National Science Foundation Mathematical and Physical Sciences divisions ASCEND program under grant award number CHE-2138107. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

References:

[1] Dard Hunter. Paper-making by hand in India. Pynson Printers, NY. 1939

[2] Dard Hunter. Paper-making in Indo-China. Mountain House Press. 1947.

[3] Dard Hunter. Papermaking: The History and Technique of an Ancient Craft. Courier Corporation. 1978.

[4] Hubbe and Bowden. Handmade paper: A review of its history, craft, and Science. Bioresources 4,4. (2009). 1736-1792.

[5] Amelie Couvrat Desvergnes. Sialkoti Paper used for the product of Pahari Drawings and Paintings in Northwest India. Artists’ Paper: A Case in Paper History. Verlgag Berger (2023) 299-334. ISBN978-3-99137-034-5

[6] El-Gendy, S.A. et al. Light and scanning electron microscopy characterization of the Egyptian buffalo hair in relation to age with analysis by SEM-EDX. Microscopy Research Technique (2023), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1002/jemt.24366